git push to Heroku, it doesn’t work.

This post is an accompaniment to my PyCon 2014 and EuroPython 2014 talk, For Lack of a Better Name(server): DNS Explained, that is a deep dive into DNS. Slides can be found here

I previously wrote a post explaining Kerberos “Like I’m 5” that turns out to be one of my most visited pieces, so I figured an ELI5 version of my DNS talk would be beneficial to some.

DISCLAIMER: Not literally for 5-year-olds! As noted with the kerberos writeup, this post is not an attempt to explain to a child. It’s meant to bring the reader from an ephemeral understanding to more comfort when fucking up working with DNS.

WTF where’s my website? #

As a nerdy person who has many side projects, I’ve had many experiences setting up personal projects for deployment. As I’m sure you have all been through, nearly every time when one does the first git push to Heroku, it doesn’t work.

All else equal - e.g. Heroku is not down - I’m betting DNS is the issue. Who actually has set up DNS cleanly the first time? You follow the directions on your host’s website to properly setup DNS records, but something still doesn’t work. We’ve all been there. And without a solid understanding of DNS, often times folks just fall into a “oh, let’s try this”, guess-editing records, waiting for DNS to propagate to test if the guess was correct - the print statements of Python debugging (I’m also guilty of this).

Naturally, curiosity got the best of me. It’s common knowledge that DNS is the internet’s phonebook. Sure - it’s the backbone of the internet; it’s a safe assumption that the cloud itself is build on DNS and duct tape, but that’s about all I knew.

Why DNS? #

So what exactly is the purpose of DNS?

DNS is necessary for you to:

- visit productive websites like reddit.com

- receive critical emails from Groupon and Gilt

- deploy your one-of-a-kind TODO list application

- allow for your corporate meme generator to not be accessible by non-employees

Truthful joking aside, DNS stands for Domain Name System, and is widely referred to being a phone book, translating human-readable names to computer-friendly addresses.

The formal description of DNS is:

… a distributed storage system for Resource Records (RR). Each DNS resolver or authoritative server stores [these records] it its cache or local zone file. A … record includes a label, class, type, and data.

– Sooel Son and Vitaly Shmatikov, University of Texas at Austin (PDF)

With the textbook definition out of the way, let’s see it in action! I always understood something better when I’ve gotten my hands a bit dirty.

Naturally, to play around, I used my latest Python crush, Scapy. Here, I am using Scapy to sniff my own DNS traffic as I am browsing the interwebs:

>>> from scapy.all import * # cringe

>>>

>>> a=sniff(filter="udp and port 53", count=10)

>>> a

<Sniffed: TCP:0 UDP:10 ICMP:0 Other:0>

>>>

>>> a.show()

0000 Ether / IP / UDP / DNS Qry "www.google.com."

0001 Ether / IP / UDP / DNS Qry "reddit.com."

0002 Ether / IP / UDP / DNS Ans "74.125.239.144"

0003 Ether / IP / UDP / DNS Ans "96.17.109.11"

0004 Ether / IP / UDP / DNS Qry "roguelynn-spy.herokuapp.com."

0005 Ether / IP / UDP / DNS Ans "us-east-1-a.route.herokuapp.com."

0006 Ether / IP / UDP / DNS Qry "roguelynn.com."

0007 Ether / IP / UDP / DNS Ans "81.28.232.189"

0008 Ether / IP / UDP / DNS Qry "www.roguelynn.com."

0009 Ether / IP / UDP / DNS Ans "roguelynn.com."

I am using Scapy’s sniff function to pick up my local traffic, filtering by the UDP protocol on port 53 (the protocol and typical port for DNS traffic), and limiting to capturing only 10 packets (or, since it’s UDP, datagrams).

So as I let this sniff function run, I went to my browser to type in roguelynn.com.

What was pretty cool as I was typing this into Chrome’s address bar, you can see a DNS query would take place for every autocomplete guess that Chrome took. It first pings www.google.com because the address bar is also Google search. Then, as I typed r, it autocompletes to reddit.com (one of my most visited sites, and therefore very natural to be guessed), and we can see the DNS query on the second line. Then as I typed ro, Chrome guesses roguelynn-spy.herokuapp.com (which is my awesome How to Spy with Python presentation, and coincidently, I am giving that talk at PyData Berlin 2014), and we can see its related query. Then it finds roguelynn.com once i typed dog and pressed enter with Chrome’s autocompletion. These autocompleted DNS queries seem more of a thing that Chrome does (and perhaps other browsers) to speed up navigation to frequented sites.

But notice one thing here: all of these DNS querys have a dot at the end, e.g.: 0009 Ether / IP / UDP / DNS Ans "roguelynn.com.". Perhaps many of you know that’s “how DNS does things”, but why is it really there?

example.com vs example.com. #

The difference between the trailing dot and the absence of such is the same difference between absolute file paths and relative file paths, e.g. ../static versus /Users/lynnroot/Dev/site/static.

Like relative filenames and directories, it can be mangled or mapped incorrectly. Depending on how your local DNS is setup, in your resolv.conf file, if there’s a line of search example.net and you navigated to example.com, the DNS search query would take the URL to not be fully qualified, and therefore would look up example.com.example.net. If you navigated to example.com., DNS would not apply the search path defined in resolv.conf.

Basically, if there is a dot at the end, it is the unambiguous, fully qualified domain name (FQDN), and not prone to search path spoofing. When playing with Scapy’s sniff function above, I didn’t put a trailing dot while navigating to roguelynn.com in my browser. Chrome’s implementation just assumes the dot, as it’s not really user friendly.

Where are my queries going? #

Continuing my curiosity, what is the route that my DNS query takes to finally get an answer for where roguelynn.com is hosted?

This is actually not that easy to figure out; once the DNS query hits my wifi router, it’s a bit of a black box where that query is forward to if it’s not locally cached. I know that my computer’s DNS is set up to 192.168.1.1, which is my router, and my router’s DNS is set up to both 75.75.75.75 and 75.75.76.76 (found this out by logging into my router’s admin page).

If I do a host query on my router’s DNS, I get the pointer to a comcast.net subdomain:

$ host 75.75.75.75

75.75.75.75.in-addr.arpa domain name pointer cdns01.comcast.net.

Now if I do a whois on the IP, I can see that Comcast, my ISP provider, owns these IP addresses:

$ whois 75.75.75.75

#

# ARIN WHOIS data and services are subject to the Terms of Use

# available at: https://www.arin.net/whois_tou.html

#

# If you see inaccuracies in the results, please report at

# http://www.arin.net/public/whoisinaccuracy/index.xhtml

#

#

# Query terms are ambiguous. The query is assumed to be:

# "n 75.75.75.75"

#

# Use "?" to get help.

#

#

# The following results may also be obtained via:

# http://whois.arin.net/rest/nets;q=75.75.75.75?showDetails=true&showARIN=false&ext=netref2

#

Comcast Cable Communications Holdings, Inc CCCH-3-34 (NET-75-64-0-0-1) 75.64.0.0 - 75.75.191.255

Comcast Cable Communications Holdings, Inc COMCAST-47 (NET-75-75-72-0-1) 75.75.72.0 - 75.75.79.255

#

# ARIN WHOIS data and services are subject to the Terms of Use

# available at: https://www.arin.net/whois_tou.html

#

# If you see inaccuracies in the results, please report at

# http://www.arin.net/public/whoisinaccuracy/index.xhtml

#

Beyond that, I do not know if Comcast’s DNS has roguelynn.com cached, and if not, where the query got directed to after that.

But DNS is hierarchical, and getting familiar with the dig command can help us understand at least how queries are resolved.

The dig command has a +trace flag that makes “iterative queries to resolve the name being looked up. It will follow the root servers, showing the answer from each server that was used to resolve the lookup."1 Let’s try this out with python.org:

$ dig +trace python.org

; <<>> DiG 9.8.3-P1 <<>> +trace python.org

;; global options: +cmd

. 12668 IN NS a.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS b.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS c.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS d.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS e.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS f.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS g.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS h.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS i.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS j.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS k.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS l.root-servers.net.

. 12668 IN NS m.root-servers.net.

;; Received 496 bytes from 192.168.1.1#53(192.168.1.1) in 221 ms

org. 172800 IN NS a0.org.afilias-nst.info.

org. 172800 IN NS a2.org.afilias-nst.info.

org. 172800 IN NS b0.org.afilias-nst.org.

org. 172800 IN NS b2.org.afilias-nst.org.

org. 172800 IN NS c0.org.afilias-nst.info.

org. 172800 IN NS d0.org.afilias-nst.org.

;; Received 430 bytes from 202.12.27.33#53(202.12.27.33) in 469 ms

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns1.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns3.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns2.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns4.p11.dynect.net.

;; Received 114 bytes from 199.19.53.1#53(199.19.53.1) in 141 ms

python.org. 43200 IN A 140.211.10.69

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns4.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns2.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns3.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns1.p11.dynect.net.

;; Received 130 bytes from 208.78.71.11#53(208.78.71.11) in 13 ms

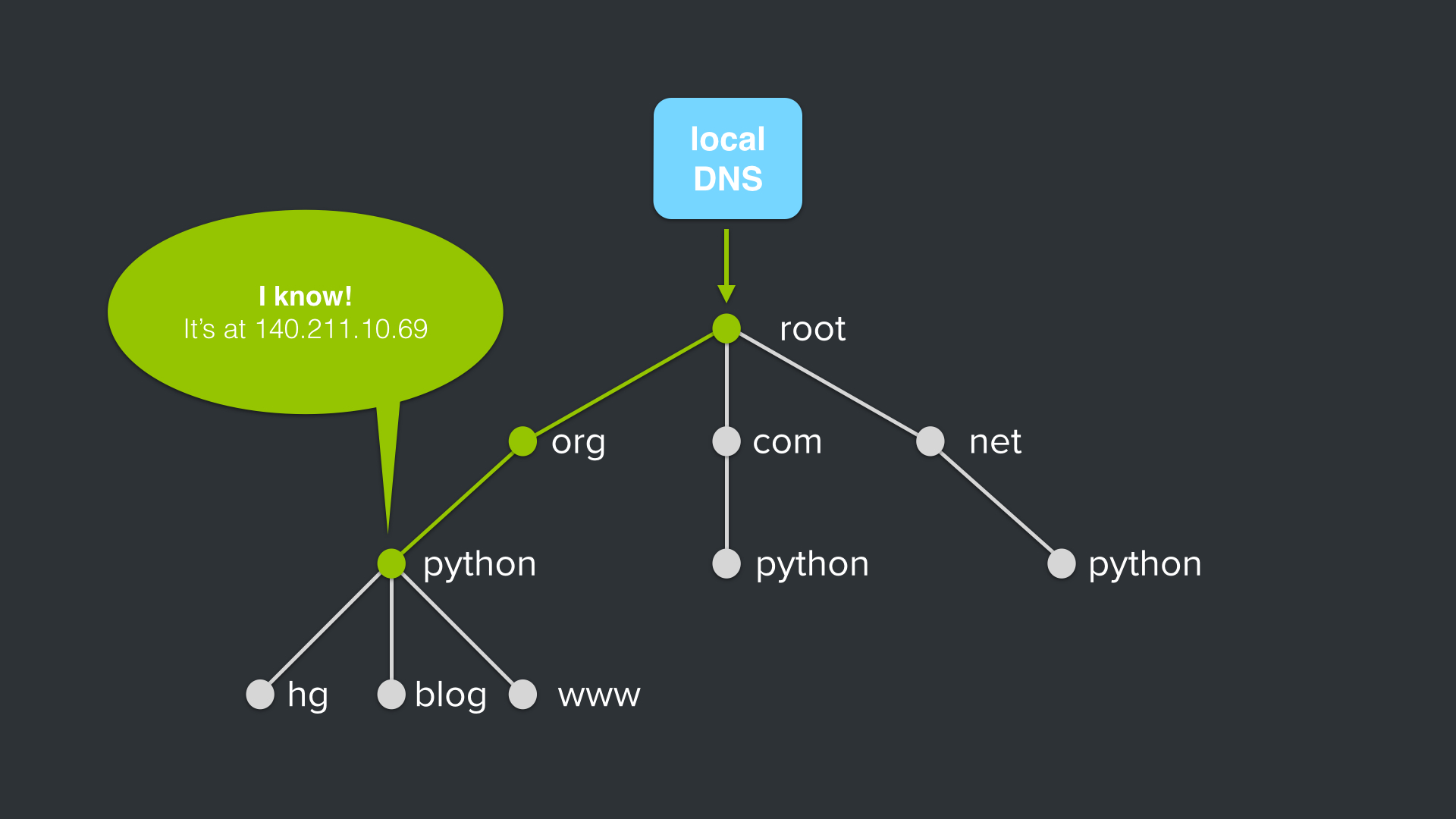

For the more visually inclined learner, let’s look at this query pictorially:

The dig query starts at my local DNS, 192.168.1.1, where, if not cached, is based on to the root server:

The query from my local DNS for python.org first asks for the root name server (the .) who knows that one of these hosts should have the information, and so the name server responds with “try one of these hosts”, which cooresponds to the .org name server:

The .org name server receives the query, then says something like “try one of these hosts” which corresponds to the python.org name server:

The python.org name server says “yep, we have the A record for python.org, and it’s at address 140.211.10.69!”

But if we wanted to know more about, say, hg.python.org, or others - doing a dig hg.python.org, we actually get that it is a CNAME record mapped to virt-7yvsjn.psf.osuosl.org:

$ dig +trace hg.python.org

; <<>> DiG 9.8.3-P1 <<>> +trace hg.python.org

;; global options: +cmd

. 12170 IN NS g.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS h.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS a.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS b.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS k.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS i.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS e.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS f.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS j.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS c.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS d.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS m.root-servers.net.

. 12170 IN NS l.root-servers.net.

;; Received 228 bytes from 8.8.4.4#53(8.8.4.4) in 145 ms

org. 172800 IN NS d0.org.afilias-nst.org.

org. 172800 IN NS a2.org.afilias-nst.info.

org. 172800 IN NS a0.org.afilias-nst.info.

org. 172800 IN NS c0.org.afilias-nst.info.

org. 172800 IN NS b0.org.afilias-nst.org.

org. 172800 IN NS b2.org.afilias-nst.org.

;; Received 433 bytes from 192.33.4.12#53(192.33.4.12) in 208 ms

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns1.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns2.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns3.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 86400 IN NS ns4.p11.dynect.net.

;; Received 117 bytes from 199.249.112.1#53(199.249.112.1) in 173 ms

hg.python.org. 86400 IN CNAME virt-7yvsjn.psf.osuosl.org.

;; Received 68 bytes from 208.78.71.11#53(208.78.71.11) in 213 ms

Other resource records #

Now there are certainly more records attached to python.org besides a CNAME pointing to hg.python.org, or blog.python.org. We can actually run the dig command against python.org with a few flags, particularly -t ANY:

$ dig +nocmd +noqr +nostats python.org -t ANY

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 25949

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 8, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 0

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;python.org. IN ANY

;; ANSWER SECTION:

python.org. 21599 IN SOA ns1.p11.dynect.net. infrastructure-staff.python.org. 2014052200 3600 600 604800 3600

python.org. 21599 IN NS ns1.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 21599 IN NS ns2.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 21599 IN NS ns3.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 21599 IN NS ns4.p11.dynect.net.

python.org. 21599 IN A 140.211.10.69

python.org. 21599 IN MX 50 mail.python.org.

python.org. 21599 IN TXT "v=spf1 mx a:psf.upfronthosting.co.za a:mail.wooz.org ip4:82.94.164.166/32 ip6:2001:888:2000:d::a6 ~all"

Unfortunately, not much came back beyond A, NS, and an MX record. If we look at pyladies.com it is a little bit more interesting, with SOA records pointing to name.com, MX records pointing to Google, and our A record pointing to our web host:

$ dig +nocmd +noqr +nostats pyladies.com -t ANY

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 50779

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 7, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 0

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;pyladies.com. IN ANY

;; ANSWER SECTION:

pyladies.com. 299 IN SOA ns1qsy.name.com. support.name.com. 1 10800 3600 604800 300

pyladies.com. 299 IN NS ns4kpx.name.com.

pyladies.com. 299 IN NS ns1qsy.name.com.

pyladies.com. 299 IN NS ns2fkr.name.com.

pyladies.com. 0 IN A 81.28.232.189

pyladies.com. 299 IN NS ns3jkl.name.com.

pyladies.com. 299 IN MX 10 ASPMX.L.GOOGLE.com.

What you won’t get when using ANY with dig is the full zone file or DNS setup, like all available CNAMEs. I’ll go a bit more into that in a bit, but for now, we can easily see the resolve path DNS takes to lookup python.org and pyladies.com. However, that is not the most efficient way that DNS can respond to queries

Caching #

Rather than inundating root and top-level name servers like . and .org, DNS can be set up to cache requests:

When a DNS resolver or authoritative server receives a query, it searches its cache for a matching label. If there is no matching label in the cache, the server may instead retrieve from the cache and return a referral response, containing [a resource record set] of the NS type whose label is “closer” to the domain which is the subject of the query.

Instead of sending a referral response, the DNS resolver may also be configured to initiate the same query to an authoritative DNS server responsible for the domain name which is the subject of the query …

– Sooel Son and Vitaly Shmatikov, University of Texas at Austin (PDF)

The authoritative server can then respond with an answer, a referral, or a failed response. After,

the authoritative server’s response … is accepted by the DNS resolver and stored in its cache only if the [resource record set] meets a set of certain conditions

which is specific to each resolver implementation.2

So if my local DNS server did not hold a cached record for python.org, it could send the DNS query to a root DNS server, and get pointed to go to the name servers that handle the .org domain. But since I’ve been to many .org sites, my DNS most likely has those name servers cached, so it can skip the first query. And then it trickles down from there.

DNS caching sounds all great and hunky-dory until you get to propagation. Propagation is how long one has to wait for DNS changes to show effect, and is often the pain point many people feel when deploying The Awesome Unique TODO App™.

DNS will hold a record for as long as its TTL - Time to Live - number, at which point it deletes it. After it’s deleted, if someone makes a new request that refers to that record, the DNS server will go through that process again, querying an authoritative server.

When setting up DNS records, perhaps your DNS host is awesome (I like name.com and fastmail.fm) and allows you to adjust the TTL within a decent range (1 second to 24 hours - tbh I’m not sure if there’s an upper limit?). However, having too high of a number set for TTL and your local and ISP caches will last longer, and therefore your friend may not be able to see your Glorious TODO App™. Likewise, having too low of a TTL may overload the server with the frequency of queries. And while your your DNS host may be awesome allowing you to find the sweet spot for TTL, some ISPs may ignore it completely and set their own expiry for records.

In addition to caching and propagation being web devs’ pain point with DNS, caching additionally opens up the ability to poison a DNS’s cache. This is by far not my area of expertise, but as I understand it, DNS cache poisoning works like so:

If a server doesn’t validate DNS responses (for example, via DNSSEC), someone could exploit that by essentially spoofing an IP address s/he owns for a given hostname, forcing visitors of that certain hostname to be directed elsewhere. To be able to spoof a DNS entry, an attacker would have to create a response faster than that of a legitimate authoritative server. Now, you can effectively DDoS a DNS caching server with probable non-cached entries, providing many attempts to send fake responses. The random domains that are now cached aren’t too useful then, but the attacker can also add to his/her response a name server for the desired domain to compromise.

Again, I am no expert in the subject of DNSSEC, so I encourage folks to read this paper (PDF) to get a better understanding of the different ways to poison a DNS’s cache.

Nerdy things I learned #

Interesting ways to interact with DNS #

dnsmap #

Earlier, we did a few dig queries with the -t ANY flag, failing to see any CNAME records. You could certainly run dig www.pyladies.com -t ANY, but it is a bit prohibitive to dig every subdomain to find information about CNAME records, especially for a site that you do not manage. As well, being able to look up the full DNS zone file is rarely allowed.

Certainly, there’s a script for that! There’s this handy tool called dnsmap that literally brute-forces subdomain lookup:

$ dnsmap pyladies.com

dnsmap 0.30 - DNS Network Mapper by pagvac (gnucitizen.org)

[+] searching (sub)domains for pyladies.com using built-in wordlist

[+] using maximum random delay of 10 millisecond(s) between requests

dc.pyladies.com

IP address #1: 81.28.232.189

sf.pyladies.com

IP address #1: 81.28.232.189

tw.pyladies.com

IP address #1: 23.23.245.47

www.pyladies.com

IP address #1: 81.28.232.189

Trying dnsmap pyladies.com only returns about 4 results even though - as one of the managers of the site - I know there’s way over 20. So don’t exactly expect the results to be comprehensive, nor fast since it’s literally searching based on a built-in word list one at a time without multithreading. So this tool is limited to its built-in word list, which you can certainly supply on your own as well.

I ran dnsmap against spotify.net for funsies while running the earlier described sniff function from scapy. Here is a captured UDP datagram in which you can see dnsmap was querying for zr.spotify.net:

###[ Ethernet ]###

dst = 04:a1:51:90:af:d4

src = 14:10:9f:e1:54:9b

type = 0x800

###[ IP ]###

ttl = 255

proto = udp

chksum = 0x12ee

src = 192.168.1.7

dst = 192.168.1.1

###[ UDP ]###

sport = 54929

dport = domain

###[ DNS ]###

id = 11102

opcode = QUERY

rcode = ok

qdcount = 1

ancount = 0

nscount = 0

arcount = 0

\qd \

|###[ DNS Question Record ]###

| qname = 'zr.spotify.net.'

| qtype = A

| qclass = IN

You can easily see the Question Record - the name of the record, type, and class.

local cache #

When I was playing around with DNS, I wanted to figure out what’s in my local DNS’s cache. At least for OS X, you can see what is cached by literally killing the process (it automatically starts up again) which flushes the cache and writes to the sys log:

$ sudo killall -INFO mDNSResponder

$ tail -n 500 /var/log/system.log | grep mDNSResponder

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 9 12229 -U- CNAME 37 1-courier.push.apple.com. CNAME 1.courier-push-apple.com.akadns.net.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 27 * 3029 -U- - PTR 0 lb._dns-sd._udp.10.0.137.10.in-addr.arpa. PTR

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 43 2869 lo0 + TXT 32 sudo\032make\032me\032a\032sammich._device-info._tcp.local. TXT model=MacBookPro10,1¦osxvers=13

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 43 2869 en0 + TXT 32 sudo\032make\032me\032a\032sammich._device-info._tcp.local. TXT model=MacBookPro10,1¦osxvers=13

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 49 70 -U- - PTR 0 13.16.16.172.in-addr.arpa. PTR

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 54 106364 -U- - Addr 0 toezmncibr. Addr

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 54 106364 -U- SOA 64 . SOA a.root-servers.net. nstld.verisign-grs.com. 2014072100 1800 900 604800 86400

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 71 106364 -U- - Addr 0 lszyeahwbnztqh. Addr

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 71 106364 -U- SOA 64 . SOA a.root-servers.net. nstld.verisign-grs.com. 2014072100 1800 900 604800 86400

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 74 * 3029 -U- - PTR 0 lb._dns-sd._udp.0.0.16.172.in-addr.arpa. PTR

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 92 * 3029 -U- - PTR 0 b._dns-sd._udp.0.0.16.172.in-addr.arpa. PTR

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 95 70 -U- Addr 4 client-log.box.com. Addr 74.112.184.96

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 95 70 -U- Addr 4 client-log.box.com. Addr 74.112.185.96

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 105 29 -U- CNAME 34 evintl-ocsp.verisign.com. CNAME ocsp.ws.symantec.com.edgekey.net.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 121 200 -U- Addr 4 www3.l.google.com. Addr 173.194.41.130

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 121 200 -U- Addr 4 www3.l.google.com. Addr 173.194.41.133

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 121 200 -U- Addr 4 www3.l.google.com. Addr 173.194.41.134

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 121 200 -U- Addr 4 www3.l.google.com. Addr 173.194.41.142

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 121 200 -U- Addr 4 www3.l.google.com. Addr 173.194.41.129

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 121 200 -U- Addr 4 www3.l.google.com. Addr 173.194.41.131

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 121 200 -U- Addr 4 www3.l.google.com. Addr 173.194.41.132

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 121 200 -U- Addr 4 www3.l.google.com. Addr 173.194.41.137

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 121 200 -U- Addr 4 www3.l.google.com. Addr 173.194.41.136

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 121 200 -U- Addr 4 www3.l.google.com. Addr 173.194.41.135

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 121 200 -U- Addr 4 www3.l.google.com. Addr 173.194.41.128

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 171 1763 -U- CNAME 24 s3.amazonaws.com. CNAME s3.a-geo.amazonaws.com.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 208 865 -U- CNAME 34 evsecure-ocsp.verisign.com. CNAME ocsp.ws.symantec.com.edgekey.net.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 211 1586 -U- Addr 4 apple.com. Addr 17.142.160.59

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 211 1586 -U- Addr 4 apple.com. Addr 17.178.96.59

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 211 1586 -U- Addr 4 apple.com. Addr 17.172.224.47

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 217 24143 -U- CNAME 38 46-courier.push.apple.com. CNAME 46.courier-push-apple.com.akadns.net.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 223 107696 -U- - Addr 0 dnsmap. Addr

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 223 107696 -U- SOA 64 . SOA a.root-servers.net. nstld.verisign-grs.com. 2014072100 1800 900 604800 86400

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 233 107019 -U- - Addr 0 dnssec. Addr

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 233 107019 -U- SOA 64 . SOA a.root-servers.net. nstld.verisign-grs.com. 2014072100 1800 900 604800 86400

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 240 25044 -U- CNAME 37 p01-calendars.icloud.com. CNAME p01-calendars.icloud.com.akadns.net.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 248 870 -U- CNAME 34 sr.symcd.com. CNAME ocsp.ws.symantec.com.edgekey.net.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 248 * 3029 -U- - PTR 0 db._dns-sd._udp.10.0.137.10.in-addr.arpa. PTR

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 267 25361 -U- CNAME 19 talk.google.com. CNAME talk.l.google.com.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 271 1271 -U- - Addr 0 ns.iana.org. Addr

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 271 1271 -U- SOA 58 iana.org. SOA sns.dns.icann.org. noc.dns.icann.org. 2014052499 7200 3600 1209600 3600

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 275 1372 -U- CNAME 24 api.facebook.com. CNAME star.c10r.facebook.com.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 279 1179 -U- Addr 4 www.evernote.com. Addr 204.154.94.81

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 298 1390 -U- TXT 32 time.apple.com. TXT ntp minpoll 9 maxpoll 12 iburst

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 311 22633 -U- CNAME 34 p15-caldav.icloud.com. CNAME p15-caldav.icloud.com.akadns.net.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 335 345 -U- CNAME 30 www.apple.com. CNAME www.isg-apple.com.akadns.net.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 351 * 3029 -U- - PTR 0 db._dns-sd._udp.0.0.16.172.in-addr.arpa. PTR

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 359 106364 -U- - Addr 0 yklgvieqhip. Addr

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 359 106364 -U- SOA 64 . SOA a.root-servers.net. nstld.verisign-grs.com. 2014072100 1800 900 604800 86400

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 366 3068 -U- CNAME 24 wildcard.tripit.com.edgekey.net. CNAME e6320.b.akamaiedge.net.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 366 1763 -U- CNAME 20 s3.a-geo.amazonaws.com. CNAME s3-1.amazonaws.com.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 371 24296 -U- CNAME 25 ocsp.ws.symantec.com.edgekey.net. CNAME e8218.ce.akamaiedge.net.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 390 25691 -U- CNAME 35 ssl.google-analytics.com. CNAME ssl-google-analytics.l.google.com.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 446 * 3029 -U- - PTR 0 b._dns-sd._udp.10.0.137.10.in-addr.arpa. PTR

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 488 25361 -U- CNAME 19 calendar.google.com. CNAME www3.l.google.com.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 493 79 -U- CNAME 17 d.dropbox.com. CNAME d.v.dropbox.com.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: Cache currently contains 106 entities; 6 referenced by active questions

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: --------- Auth Records ---------

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: Int Next Expire State

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 8 0 0 ALL 32 sudo\032make\032me\032a\032sammich._device-info._tcp.local. TXT model=MacBookPro10,1¦osxvers=13

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 8 0 0 lo0 30 1.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.8.E.F.ip6.arpa. PTR sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 8 0 0 en0 30 13.16.16.172.in-addr.arpa. PTR sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 8 0 0 lo0 16 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local. AAAA FE80:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0001

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: 8 0 0 en0 4 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local. Addr 172.16.16.13

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: --------- LocalOnly, P2P Auth Records ---------

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: State Interface

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: Verified LO 36 sudo\032make\032me\032a\032sammich._whats-my-name._tcp.local. SRV 0 0 0 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: Shared LO 7 b._dns-sd._udp.local. PTR local.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: Shared LO 7 r._dns-sd._udp.local. PTR local.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: KnownUnique LO 11 1.0.0.127.in-addr.arpa. PTR localhost.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: KnownUnique LO 11 1.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.ip6.arpa. PTR localhost.

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: --------- /etc/hosts ---------

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: State Interface

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: KnownUnique LO 4 localhost. Addr 127.0.0.1

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: KnownUnique LO 16 localhost. AAAA 0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0001

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: KnownUnique 1 16 localhost. AAAA FE80:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0001

Jul 21 08:34:42 sudo-make-me-a-sammich.local mDNSResponder[60]: KnownUnique LO 4 broadcasthost. Addr 255.255.255.255

# <--snipped-->

We can see some familiar records; I see Facebook, Evernote, Apple, Tripit, Amazon - names I would expect since I use apps that all connect to those services.

What is that I hear? Not enough Python? Well…

Twisted #

Surely you knew this was coming - you can easily create your own DNS forwarder with Twisted’s names.

Below is a simple DNS server from Twisted’s documentation. We can run this, as well as fire up scapy, and run dig against the server:

from twisted.internet import reactor

from twisted.names import client, dns, server

def main():

"""

Run the server.

"""

factory = server.DNSServerFactory(

clients=[client.Resolver(resolv=‘/etc/resolv.conf')]

)

protocol = dns.DNSDatagramProtocol(controller=factory)

reactor.listenUDP(10053, protocol)

reactor.listenTCP(10053, factory)

reactor.run()

if __name__ == '__main__':

raise SystemExit(main())

Looking at the datagram picked up by scapy, we can see that the query - the Question - has a query name, type, and class:

###[ Ethernet ]###

dst = 04:a1:51:90:af:d4

src = 14:10:9f:e1:54:9b

type = 0x800

###[ IP ]###

ttl = 64

proto = udp

chksum = 0x4a0c

src = 192.168.1.7

dst = 192.168.1.1

\options \

###[ UDP ]###

sport = 33408

dport = domain

###[ DNS ]###

opcode = QUERY

rcode = ok

\qd \

|###[ DNS Question Record ]###

| qname = 'python.org.'

| qtype = A

| qclass = IN

And now the corresponding response with the DNS resource record and data associated with it, include type of record, TTL, data, and resource record name:

###[ Ethernet ]###

dst = 14:10:9f:e1:54:9b

src = 04:a1:51:90:af:d4

type = 0x800

###[ IP ]###

ttl = 64

proto = udp

chksum = 0xb74c

src = 192.168.1.1

dst = 192.168.1.7

###[ UDP ]###

sport = domain

dport = 54438

###[ DNS ]###

qr = 1L

opcode = QUERY

\qd \

|###[ DNS Question Record ]###

| qname = 'python.org.'

| qtype = A

| qclass = IN

\an \

|###[ DNS Resource Record ]###

| rrname = 'python.org.'

| type = A

| rclass = IN

| ttl = 39777

| rdlen = 4

| rdata = '140.211.10.69'

Interesting ways to use DNS #

Anycast #

You folks may know the types of IP network addressing methodology, including unicast, multicast, and broadcast, or at least somewhat familiar with those terms when screwing setting up networking for a local VM (vagrant is so uber helpful to avoid these networking issues, btw!).

Anycast is a fourth one where datagrams are sent via a single sender to a group of potential receivers all identified by the same address, referred to as a one-to-nearest association. One of the keynotes at PuppetConf 2013 by Google’s Gordon Rowell goes into great explanation about how Google takes advantage of anycast. Google uses it for its public DNS servers, the all familiar 8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4, where someone’s DNS lookup of 8.8.8.8 in Australia may be routed somewhere different than coming from the US, but still receives the same information. Google configures their applications for Anycast, and it allows for folks in operations to take down one cluster and reroute traffic to another, leaving folks to not have to worry about getting the same data when looking up 8.8.8.8. TL;DR: It’s great for load balancing.

DANE #

DANE stands for DNS-based Authentication of Named Entities. It’s a protocol for certificates to be bound to DNS names using DNSSEC. It can be likened to two-factor authentication that we, as users, are familiar with. Essentially, DANE is a proposed way to cross-verify the domain name and the CA-issued certificate. 3

The issue that DANE solves is the inability to verify that the organization running the web server officially owns the domain name. As well, the DNS record does not contain information regarding which Certificate Authority is preferred by this organization.

Exploits of this weakness was seen twice in 2011 with Comodo and the Dutch CA, DigiNotar, where false certificates were generated giving the attackers the ability to perform man-in-the-middle exploits.

So again, what DANE does is provide a way to cross-verify the domain name information with the host’s CA-issued certificate. The pieces of authentication with respect to two-factor auth is:

- a DNSSEC-authenticated authoritative DNS entry about the valid certificate, and

- the actual certificate - or a hash of the certificate - with the valid fully-qualified domain name that can be validated by a trusted CA.

DNSSEC is required to be configured on your authoritative DNS server for DANE to be set up properly. With that, you just need to make a TLSA (TLS trust anchor) record with information on the type of certificate used, the hash of the certificate, and the hash function used, among other things, like so:

_443._tcp.www.example.com. IN TLSA ( 0 0 1 91751cee0a1ab8414400238a761411daa29643ab4b8243e9a91649e25be53ada )

For funsies, let’s take a look at one of the available DANE test sites:

$ dig -t TLSA _443._tcp.www.fedoraproject.org

; <<>> DiG 9.8.3-P1 <<>> -t TLSA _443._tcp.www.fedoraproject.org

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 51776

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 0

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;_443._tcp.www.fedoraproject.org. IN TLSA

;; ANSWER SECTION:

_443._tcp.www.fedoraproject.org. 299 IN TLSA 0 0 1 19400BE5B7A31FB733917700789D2F0A2471C0C9D506C0E504C06C16 D7CB17C0

;; Query time: 115 msec

;; SERVER: 8.8.8.8#53(8.8.8.8)

;; WHEN: Mon Jul 21 14:26:39 2014

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 96

As of writing this post, dnspython supports DANE with the ability to create and manage TSLA resource records, and Twisted is currently working on EDNS and DNSSEC support, with the goal of including DANE.

Service Discovery #

Another nerdy nugget of awesomeness that I uncovered during my deep dive into DNS is that it can be used for service discovery.

There are a few ways and tools to implement service discovery, but it ultimately boils down to the question, “What servers run this service?” As mentioned, one can leverage DNS to help us answer this question with the use of SRV records. SRV records within DNS zones map canonical names, typically in the form of _name._protocol.site, to hostnames.

For instance, Spotify leverages the service lookup ability. Each service has its own SRV record, with one record canonically named after the service itself. When you spin up a Spotify client, it does an SRV lookup, similar to this dig command:

dig +short _spotify-client._tcp.spotify.com SRV

10 12 4070 AP1.spotify.com.

10 12 4070 AP2.spotify.com.

10 12 4070 AP3.spotify.com.

10 12 4070 AP4.spotify.com.

The service look up continues on, since user clients connect to an access point, for example AP1.spotify.com, and then the access point resolves the service that the client is looking for, e.g. user service for the user’s profile information:

DHT Ring #

The last little nugget I discovered is the ability to store a DHT ring within DNS.

DHT stands for Distributed Hash Tale. It basically gives you a dictionary-like interface, or a key-value store, but the data or nodes are distributed among a network.

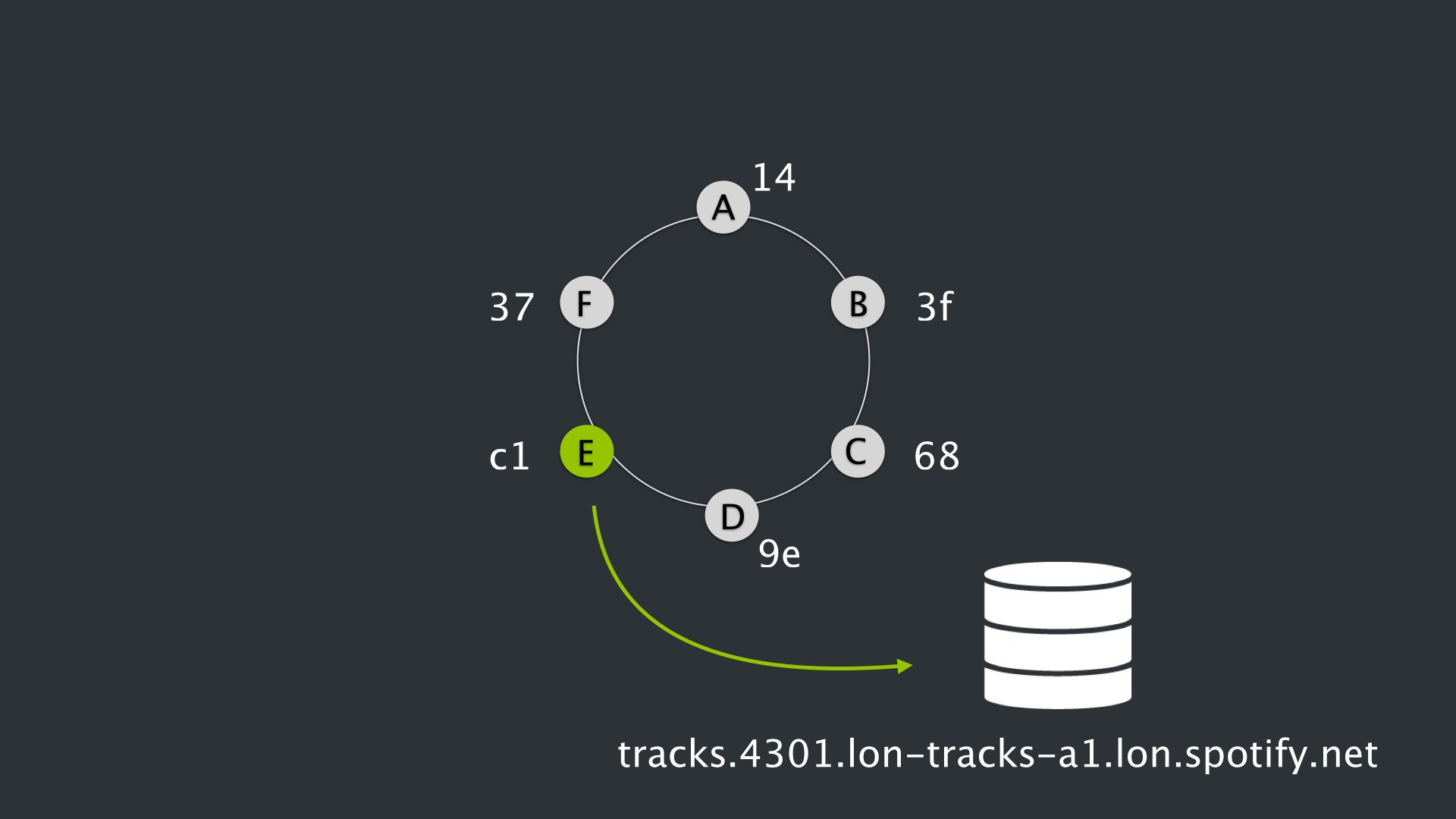

Looking at Spotify again, we store some service configuration data in a DHT ring within DNS TXT records.

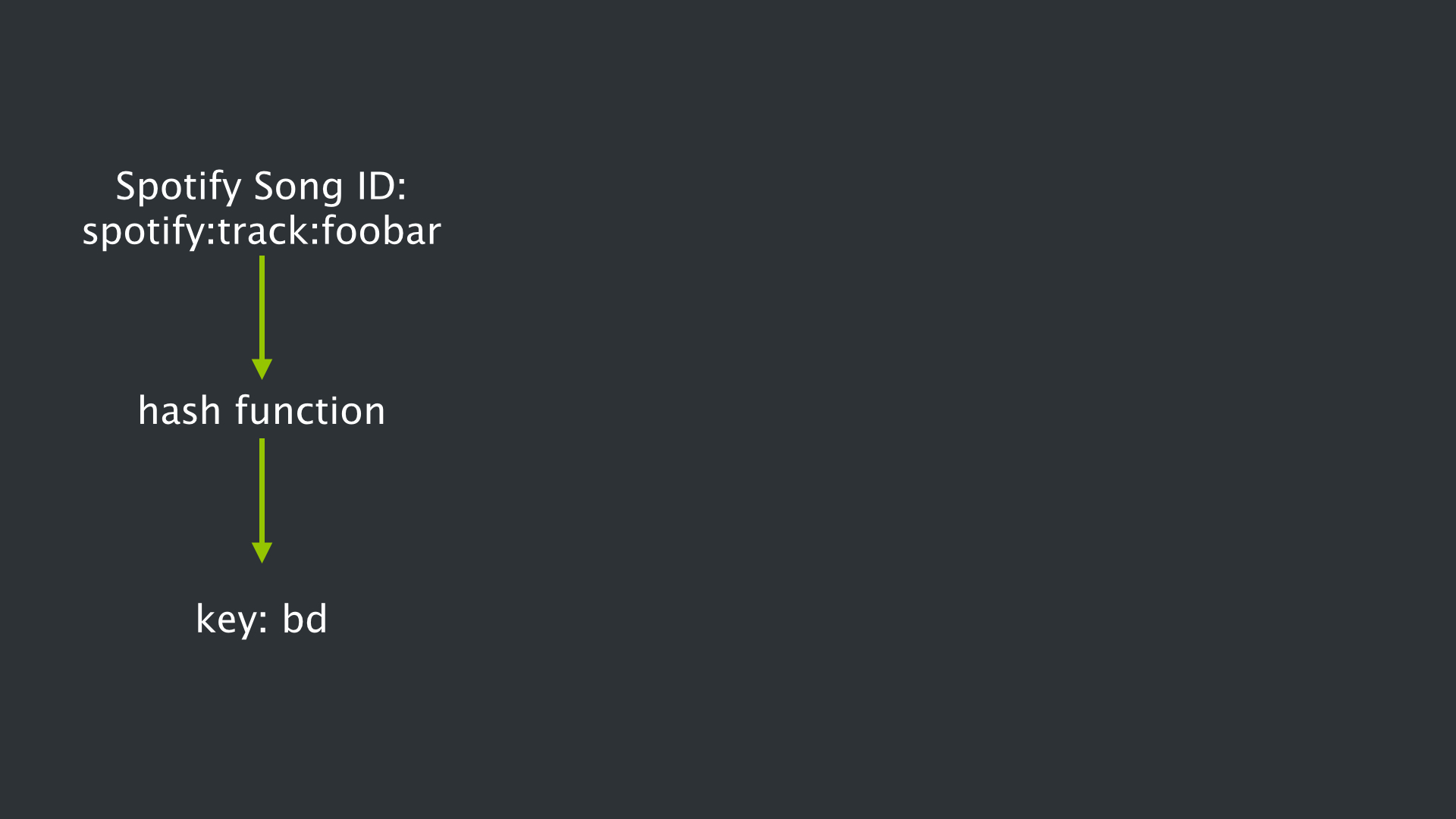

So for example, when you are on the Spotify client, and want to play a particular song named “foobar” (one that has not yet been locally cached on your machine), the client performs a lookup. When it does, the song ID is hashed, which then becomes the key within the DHT ring.

So that particular key is then looked up within the DHT ring that is stored in DNS. The value associated with that key is essentially the host location of the service where that song and/or its relevant information/metadata is located. So in this case, Instance E owns (9e, c1], which is where this particular Spotify track, foobar, lives, and is mapped to a particular hostname and port.

And then Instance E is mapped to a hostname, for example tracks.4301.lon-tracks-a1.lon.spotify.net which would be the machine that houses data on the foobar track.

The dummy hostname, tracks.4301.lon-tracks-a1.lon.spotify.net, tells me that this machine hosts information on tracks, can be connected to via port 4301, is located in our London data centers, and is in pod a1.

Confusing, I know – we’re essentially using DNS for a DHT ring to leverage the distributed characteristic of a DNS system.

TL;DR DNS is hard #

I threw a lot at you - DNS by no means is easy to get and understand in a single blog post. And I definitely guarantee you, you will still screw up your deployment configuration again, because DNS is hard. It’s a black box particularly because it’s not easy to debug. It’s not only hard to learn and debug, but it’s hard to limit it to a 30 minute talk. Hopefully this write up and accompanied video leaves a better understanding of DNS.